Originally published on LinkedIn in July 2018.

I’m not big on titles. I’m a guy who likes doing everything and trying everything. And titles really get in the way of a person who likes trying things out, playing with things, and figuring out how things work.

But people need to know what the hell to call you, because it’s just how humans are. And because “Editor” is just too damn specific a title, I instead use “Content Producer and Manager”. It perfectly encapsulates all the weird stuff I do, and people don’t seem to require any explanation as to what it means.

Most excellent, dude.

So what do Content Producers/Managers do? Among other things:

Outlining and/or preparing content and production pipelines; budgeting; preparing timelines, deadlines, and workflows; setting up editorial guidelines; writing articles; delegating tasks; managing content management systems and customer relationship management systems, sub/copy/structural editing; engaging in audio/video production; doing social media work including SEO via Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, etc.

You should be willing to throw yourself at a problem and enjoy figuring it out. And enjoy trying different approaches until something finally works.

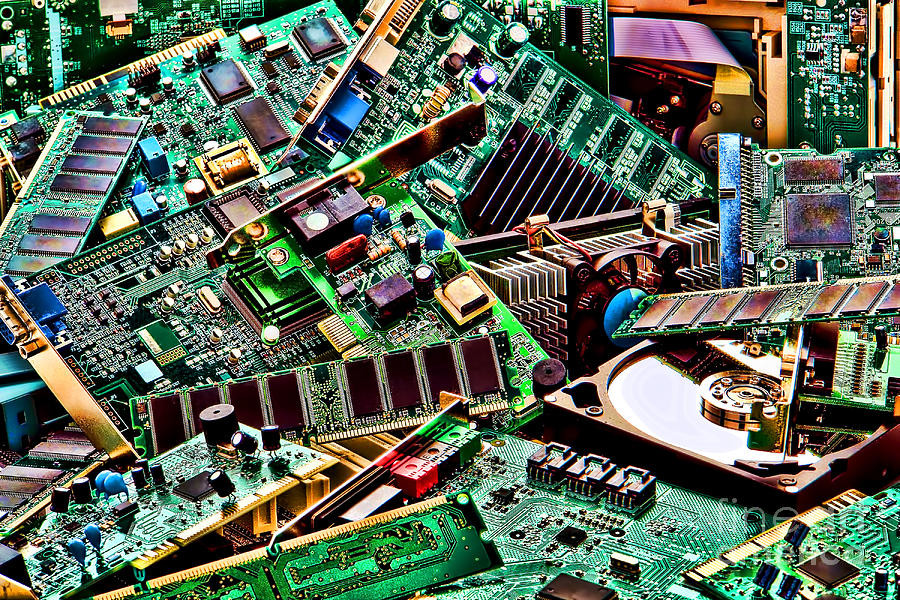

It’s no surprise that people in this kind of role tend to enjoy playing with hardware and software. Me? I really enjoy playing with computers. To figure out how a program works. To solve a hardware problem. Fix a bug. Or in some cases: stress-test a machine. I have fond memories from my teenage years of hex-editing the Recycling Bin off the Windows 95 desktop, stress-testing an Alpha running NT 4 and making it hang by running Notepad, Winamp, and EverQuest at the exact same time.

This is the sort of possibly unusual behaviour that is often exhibited by gamers, particularly once we start playing with user-made modifications for games and find ourselves having to use programs such as Load Order Optimisation Tool (LOOT) or The Elder Scrolls 5 Edit (TES5Edit), or numerous other programs to make a mod work properly.

This inquisitive tendency of course bleeds into other areas of life. Like tonight, when I was trying to load an eBook onto my iPad Mini. And it just wasn’t working.

So I threw the file onto my Google Drive. Surely Google Drive should work once I’ve autogenerated a unique link. Nope. No dice. Safari and Chrome alike were having none of it.

Transferring the file via Bluetooth and USB? No way hose.

AirMore allowed me to copy the file across. But Apple doesn’t like letting users freely roam around the hard-drive of their products. So once again: a dead end.

Dropbox seemed a logical option, but the OS on my iPad? Too old. Can’t install the app.

Until it occurred to me: I…don’t need the app. Logging in should be sufficient to access my Dropbox files.

And lo and behold, finally, having uploaded the book to my Dropbox account allowed me to successfully download it and copy it to my iBooks folder. All via a web-based interface. Bazinga!

Now I can finally read the book I got. 400 or so glorious pages about the study of archaeology. Because archaeology is cool.

This sort of obsessive need to problem solve may not be conventional behaviour. But then, neither is our job. We like to know that if there’s a hiccup along the way, that we can find a solution to ensure that everything continues working. Which means we need to be willing to learn, know how to research information, and be able to think creatively.

It’s not for everyone. But I think it’s incredibly fun, being a content manager/producer. I get to help people out with their goals, tinker, think on my feet, play with computers, and jump between numerous and not necessarily related tasks.

It’s pretty freakin’ rad.