Core Ideas

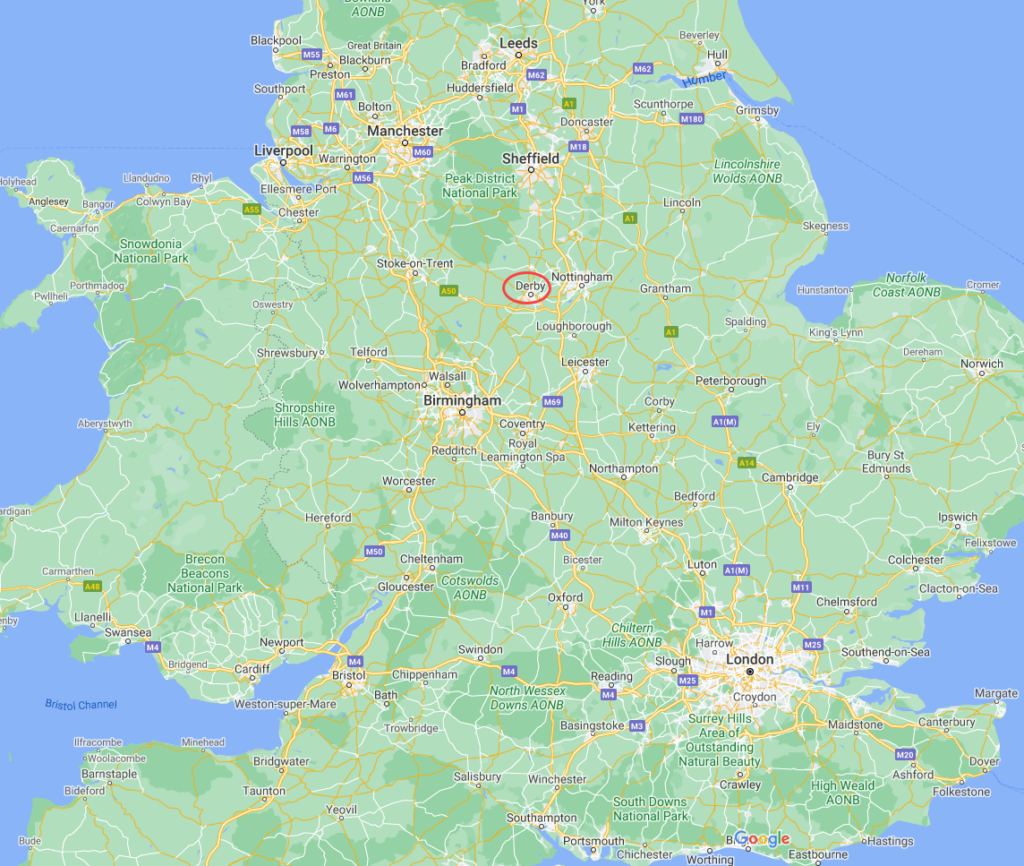

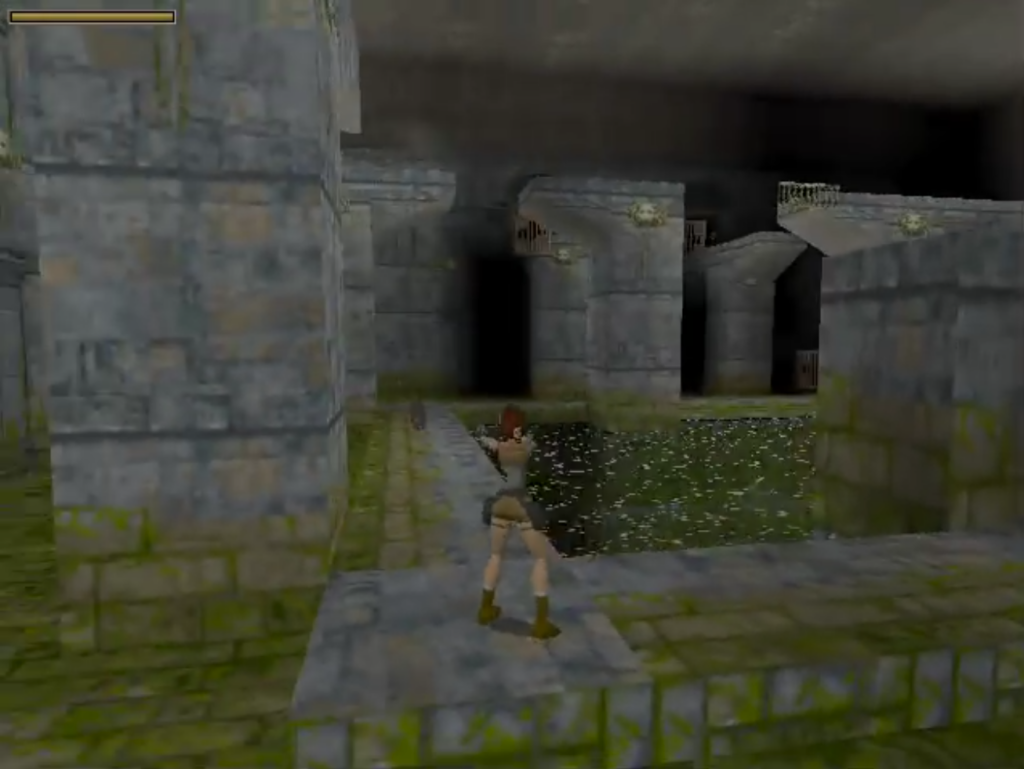

Tomb Raider was released in 1996 and spanned six games, all produced by Core Design Pty Ltd., in Derby, England. The six series in this game are: Tomb Raider, Tomb Raider II, Tomb Raider III, Tomb Raider: The Last Revelation, Tomb Raider Chronicles, and Tomb Raider: The Angel of Darkness. For the purposes of maintaining a firm grip on sanity, it is referred to here as the Core Series – a reference to the founding studio.

A Legend Reborn

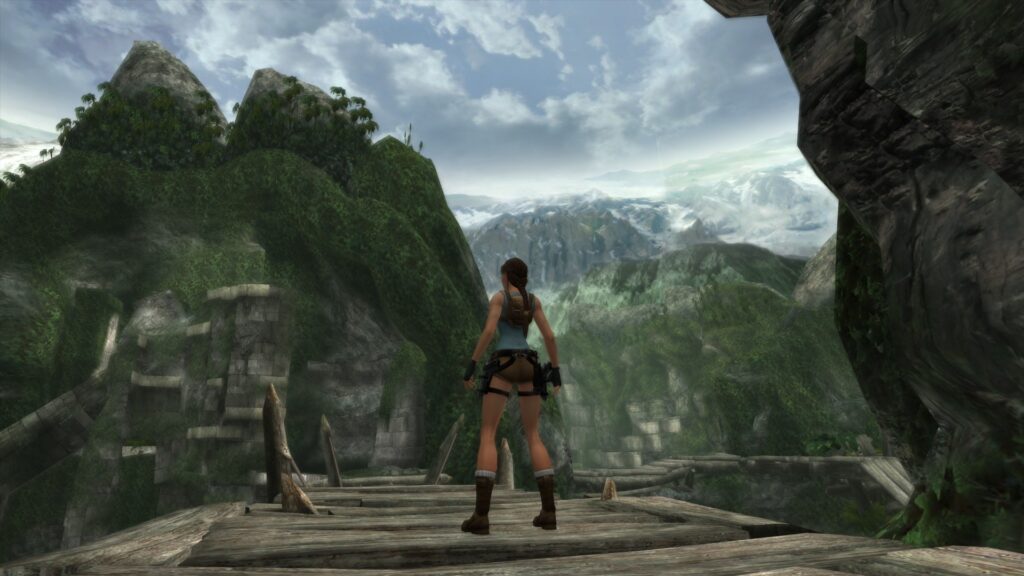

Following the critical and arguably financial failure of Tomb Raider: The Angel of Darkness, Tomb Raider publisher Eidos Interactive handed the license for Tomb Raider over to American game studio Crystal Dynamics, who rebooted in the series with the 2006 release, Tomb Raider: Legend (referred to here as the Legend Series). From 2006 to 2008, three new Tomb Raider games were released in the Legend series: Tomb Raider Legend, Tomb Raider Anniversary, and Tomb Raider Underworld. This trilogy of games utilised a game engine commonly referred to as the Horizon Engine.

Survivor’s Story

In 2013, the Tomb Raider series was rebooted a second time. The title of the first game out the door was, to the confusion of more than a few people, simply Tomb Raider. Two sequels followed on its heels – Rise of the Tomb Raider and Shadow of the Tomb Raider. This trilogy is referred to here by the nickname provided by the Tomb Raider community – the Survivor Series. The engine used for this trilogy of games evolved from the Horizon Engine into a new engine of its very own, called the Foundation Engine.

Bear in mind, also, that each iteration of the series has changed Lara’s background and given her a new backstory, so don’t go looking for “canonicity” here. You’re not going to find any, aside from a cute stinger at the end of Shadow of the Tomb Raider, which ends with players seeing a letter on her desk from Jacqueline Natla (the antagonist from the very first Tomb Raider).

Core Design

Tomb Raider was built and produced in 18 months by Core Design Ltd., a team of six based out of Derby, England. Their publisher? Eidos Interactive. Derby is located in Derbyshire, in the East Midlands of England (smack in the middle of the country). It’s kind of important. To give you a sense of just how much of an impact the series had on Derby – there’s an actual road named after her. A local election voted in favour of naming a street after a videogame character designed by a local team of developers. Six developers, in fact. Gavin Rummery, Jason Gosling, Toby Gard, Heather Gibson, Neal Boyd, and Paul Douglas. However, Toby Gard is cited as the person responsible for creating Lara herself.

Creating Lara

Lara started out as an unnamed male character. Early iterations of the character featured a fedora and whip – an obvious homage to Indiana Jones, who has been cited as an inspiration for the series. Fearing a potential lawsuit, the sex of the character was quickly changed, and Laura Cruz was born. She would eventually be renamed Lara Croft to sound a bit more familiar to British ears. As Croft’s creator Toby Gard explained in a documentary, the team at Core went through a local phonebook looking for names that might sound better, and several were identified as potentials until finally the team agreed on “Croft”.

Indiana Jones was not, interestingly, the only influence upon the game. The original platformer that arguably created the cinematic platforming genre – Prince of Persia – was cited by Croft creator Toby Gard as an influence during the creative process of making the first Tomb Raider, as well as two other games one might not expect to see mentioned: Virtua Fighter and Ultima Underworld. As Gard explained in an interview, he wanted to combine these two games. Outside of gaming, the films Tank Girl, Indiana Jones, and Hard Boiled (the John Woo film) all helped give Gard “the idea for Lara”.

But success was not assured. 3D gaming was still a new frontier in the mid-1990s. Which is why, as explained in a comprehensive and highly recommended Eurogamer piece, “Eidos had budgeted for launch sales of 100,000 units. After those sold out, shops called for hundreds of thousands more copies. Tomb Raider went on to sell 7.5m”.

Core Design would go on to produce five more games after the release of the first Tomb Raider game. So taken was Eidos by the staggering success of the series, that they demanded Core have a new game ready each year in time for the Christmas holiday season.

Each subsequent game would tweak the formula and add new features, but all utilised the same engine (dubbed the “TRosettaStone Engine”). A punishing yearly release schedule hindered innovation, and though the sequels performed well, over time it became clear that the engine was getting long in the tooth, the franchise formula was becoming stale, and that change was needed. Gard, famously, left after the release of the first game, citing disappointment with the way in which Lara was marketed as the driving reason.

Thus, after the critical drubbing of the sixth entry in the series, Tomb Raider: The Angel of Darkness, Eidos Interactive took the license away from Core and handed it to it to US-based studio Crystal Dynamics, who are based out of the San Francisco bay area. Crystal Dynamics have produced every single game in the series since barring the latest release, Shadow of the Tomb Raider, which was produced by a third studio: Eidos Montreal (Crystal Dynamics provided additional development for the game, but the primary development studio was Eidos Montreal).

Core Design’s story did not quite end there, however. An attempt was made internally to design their own “anniversary” edition of Tomb Raider – and video footage of this game did eventually leak to the Internet and can be found easily. However, that game would ultimately be scrapped, and Crystal Dynamics would later release (in 2007) Tomb Raider Anniversary, the second game in the Legends trilogy.

And yet.

In the beginning, it all started with a small team of six people.

In a regional English city.

Together, a small team of six developers created one of the most iconic videogame characters to ever grace PCs and consoles. An impressive legacy.

The Technology Context

Gaming and technology in 2020 is a far, far different world from that of 1996. Where now players have digital purchasing platforms, gamers in the mid-90s had to buy games from brick and mortar stores, and the content had to fit onto the spaces available on discs at the time. It’s not like today, where games can be as big as they need to be and purchased through platforms such as Good Old Games, Steam, Origin, or the Epic Store, where games like Kingdom Come: Deliverance can clock in at 75 gigabytes, or – *screams internally* – Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, which takes up a terrifying 209 gigabytes. At the time, it was common to fit a game onto a single, 650Mb CD. No director’s cut here. Core Design had to make peace with the technological limitations and craft a story that works within those confines.

Absent any ability for the game to provide more information than is physically possible, we’re left with a game that is forced to tell us a story through its environments, and what the state of those environments suggest to players.

Of course, some games required more space. Baldur’s Gate was an impressive five-CD install. Blade Runner spanned four CDs. The Curse of Monkey Island? Two CDs. Ditto for Dark Forces II: Jedi Knight. Tomb Raider, however, shipped on one CD across all the platforms for which it was released (Playstation and Saturn).

Not unlike contemporary games, Tomb Raider featured a multi-platform release – both of which had the kind of game controller support that was (and still is) lacking from for the PC edition of the game. Want to give your pinkie a workout it’s not likely to forget anytime soon? Have a go at the original Tomb Raider.

The PC edition is widely regarded as the best of the three options, primarily on account of it having a Save Anywhere system. The console editions of the game, being mindful of available hard drive space, had save crystals, which allowed players to only save once per level.

That’s 15 saves total.

As each level can take upwards of an hour to complete, this was for many a point of considerable annoyance. And understandably so.

There is a lesson, a point, to this. The technology available at the time placed restrictions on the developers at Core Design. Would they have liked to have the ability to expand the story a bit further? By all accounts, the answer seems to learn towards “yes”, as at least one full motion video (FMV) was known to have been cut from the game, and Gard himself has alluded to wanting to have made plot points in the game clearer.

Characters/Story

Plot

British treasure hunter Lara Croft is hired by American businesswoman Jacqueline Natla to locate one of the three pieces of the Scion of Atlantis (a pendant broken up into three pieces). After locating the first piece, one of Natla’s mercenaries attempts to betray Lara. This results in Lara seeking out the remaining pieces, interrupting Natla’s plans and becoming enmeshed in an ages-old conflict.

Characters

What plot there is includes a rather small cast of characters – 11 in total, including one character who only appears as a voice-over during a cut scene.

Lara Croft: the protagonist of the game, an English aristocrat and treasure hunter.

Jacqueline Natla: a wealthy businesswoman who hires Lara to find one of the three pieces of the Scion. For reasons that have never made much sense or been very clear, she betrays Lara by sending one of her henchmen, the mercenary Larson, to kill her and take her the piece Lara locates in Peru.

Qualopec: one of the three rulers of Atlantis, whose grave is located in Peru.

Tihocan: one of three rulers of Atlantis, whose grave is located in Greece.

Larson: an American mercenary who works for Natla.

Pierre Dupont: a French mercenary and treasure hunter.

Carlos: Lara’s Peruvian guide.

Brother Herbert: a monk who wrote about the potential burial site of Tihocan.

Bald Man: one of Natla’s henchmen.

Skater Boy: one of Natla’s henchmen.

Cowboy: one of Natla’s henchmen.

Levels

The game: Tomb Raider is broken up into four distinct areas, with a total of 15 levels spread across those four regions: Peru, Greece, Egypt, and finally Atlantis.

Peru: Caves, City of Vilcabamba, The Lost Valley, Tomb of Qualopec

Greece: St. Francis’ Folly, Colosseum, Palace Midas, Cister, Tomb of Tihocan

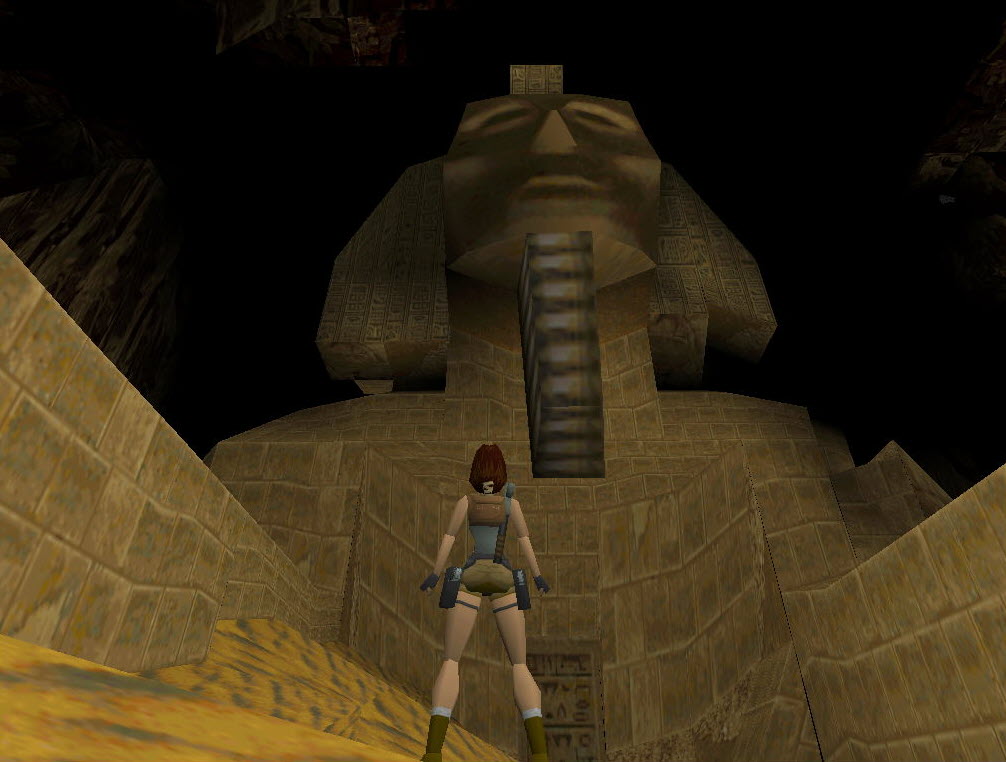

Egypt: City of Khamoon, Obelisk of Khamoon, Sanctuary of the Scion

Atlantis: Natla’s Mines, Atlantis, The Great Pyramid

Who is Lara Croft?

“Entertainment evolves generationally.”

– Filmjoy, Mikey Neumann

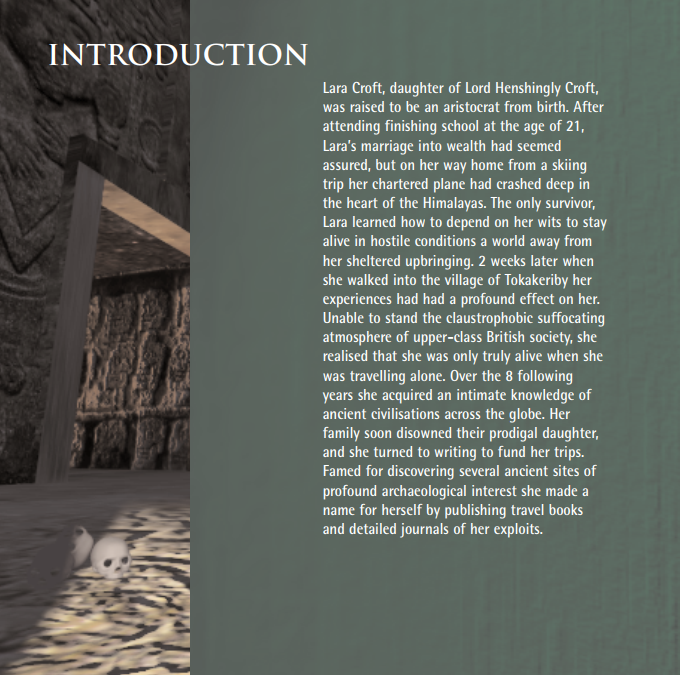

Manual Gaming

One of the fascinating things about the way games from the 90s operated is that they had limitations. Aside from obvious graphical and design limitations, games were also constrained by the technology on which they were deployed. At the time, that meant CD-ROMs. So somewhere between 650-700MB of data.

These restrictions meant that players would have to turn to game manuals to obtain background information on the games they were playing, be it information about the world or the characters they were playing.

In the case of Lara Croft, the first Tomb Raider game doesn’t provide players with much in the way of character history. Nor does the game challenge or reward players for engaging in different playing styles. Whether or not you choose to kill every wolf, bear, bat, crocodile, and velociraptor that comes your way makes no difference in the eyes of the game. An RPG it is not.

Instead, players are left do something absolutely shocking – read the instruction manual. Doing so will reveal an interesting bit of background context as to who Lara is and why she gets up to her tomb raiding hijinks. This is worth noting given the focus placed on developing Lara’s background and characterisation in the Legend and Survival timelines.

Raiding Manual, 1996

So who is Lara Croft?

Well, she is in fact “the daughter of Henshingly Croft, [Lara] was raised to be an aristocrat from birth. After attending finishing school at the age of 21, Lara’s marriage into wealth had seemed assured, but on her way home from a skiing trip her chartered plane had crashed deep in the heart of the Himalayas. The only survivor, Lara learned how to depend on her wits to stay alive in hostile conditions a world away from her sheltered upbringing.

Two weeks later when she walked into the village of Tokakeriby her experiences had had a profound effect on her. Unable to stand the claustrophobic suffocating atmosphere of upper-class British society, she realised that she was only truly alive when she was travelling alone. Over the 8 following years she acquired an intimate knowledge of ancient civilisations across the globe.

Her family soon disowned their prodigal daughter, and she turned to writing to fund her trips. Famed for discovering several ancient sites of profound archaeological interest she made a name for herself by publishing travel books and detailed journals of her exploits.”

(I’m not even kidding. That’s from the actual manual.)

This is how we did things in the 90s. We didn’t bother trying to explain the plot to you within the game! There wasn’t enough space on the disc for such conveniences! Remember Diablo? Starting the game results in players picking a few basic details about their characters, arriving in Tristram, and then learning about everything else as they went along.

It was by reading the manual that more could be learned about Khanduras, King Leoric, the Sisters of the Sightless Eye, the Brotherhood of the Vizjerei, The Great Conflict, the Sin War, etc. Reflecting the narrative constrictions placed upon games in the 90s, user manuals operated as a must-have to properly understand a game’s lore and character information.

Survivor’s Manual

Whereas the manual for the original Tomb Raider gave us an idea of the character, the manual for the first game in the Survivor series, by comparison, gave us something closer or akin to a synopsis of the game:

“Tomb Raider is the first chapter in the story of Lara Croft. As the game begins, Lara is a young college graduate, eager to find adventure and make her mark on the archaeological world. With her best friend Sam, Lara joins an expedition aboard the research vessel Endurance in search of the lost kingdom of Yamatai.

Thought to have existed on an island somewhere off the coast of Japan, Yamatai’s true location has remained a mystery for centuries. Trusting in Lara’s research, Conrad Roth, captain of the Endurance, takes the expedition into a dangerous area of the sea known as the Dragon’s Triangle. It is here that everything goes horribly wrong and Lara discovers the true price of adventure.”

The Survivor series, being a modern series with more disc space for brick and mortar editions (to say nothing of digital download editions, which in theory do not have space constraints[1]), can focus on a more robust amount of character progression and growth in-game. Whether or not the game succeeds is, of course, a more subjective point.

Other games at the time found different ways to bring players up to speed on their story and characters. For example, Star Wars: Dark Forces, a Doom clone, used the famous Star Wars opening crawl to bring players up to speed on the plot. The sequel, Dark Forces II: Jedi Knight, utilised FMVs across two discs to tell a more grandiose – and comprehensive – story.

Between the Core Series and the Survivor Series, there also existed a trilogy of games known as the Legend Series. We’ll get back to that shortly.

Gameplay

As Mikey Neumann pointed out in a piece on Blade Runner 2049, “entertainment evolves generationally”, so the expectations of audiences in the mid-1990s are not the same as those of audiences in 2020. So let’s talk about the gameplay, shall we?

In 1996, it was necessary for a game with limited disc capacity to use the game world to tell the story. After two FMVs that set up the story, the game officially begins in Peru. As the FMV comes to a close, a pair of doors swing shut behind Lara as she looks out onto a snowy tunnel extending before her.

Throughout most of the first part of the game there’s little to no real music, no real narrative propulsion. There’s no journal or quest menu, no specialised button that highlights important objects or characters. Instead, players are left to explore the astonishingly massive set of levels that comprise the Peru section of the game. Tomb Raider invited players to observe the surroundings and figure things out on their own. The emphasis in the first game is decidedly on “exploration”. As designer Gard himself said once in an interview: “Tomb Raider is essentially about solving mysteries and exploration and these will always be interesting.”

The first two regions of the game, Peru[2] and Greece, place a heavy focus/emphasis on exploration. It’s also quite low on combat. This reflects designer Toby Gard’s feelings on killing in games. “Well the explanation’s dead simple really,” Gard explained in an interview with Gamasutra. “I wanted the game to start off with enemies that were reasonably realistic so that the player could begin to believe in the Tomb Raider world and hopefully be more surprised when it all went weird at the end. The problem was that we knew it would be really hard to put in lots of believable human characters because they’d be so immobile in comparison to Lara. I’m also not keen on just mindlessly killing humans in games anyway. So it had to be dangerous animals”.

It is fascinating to note that Gard’s iteration of Tomb Raider features far fewer humans than any other game in the series. It manages to easily avoid the ludo-narrative dissonance that plagued later sequels and iterations of the game by making Lara’s foes primarily ones found in nature – bats, wolves, bears, jackals, hyenas, and – *checks notes* – skinless Atlantean Centaurs and gargoyles.

By modern standards

By 2020 standards Tomb Raider would most likely frustrate players, with its random placement of switches in seemingly random locations that open doors and barricades in unlikely and sometimes distant locations, forcing players to return (sometimes frequently) to previously visited locations. For example, early in the game whilst exploring a beautiful underwater location, the player is required to pull on a lever that throws open a hatch that leads into a small home. A later level, based in a mine, features a hidden room above a mine cart tunnel with a switch that needs to be pulled to open a wooden door that’s hidden behind a waterfall.

Why the disparate placement of levers? Why have a trapdoor inside a house that leads into an underwater tunnel? Who knows? The puzzles in Tomb Raider rarely make much sense. They exist to prompt exploration, not to reflect the culture being, uh, tomb-raided.

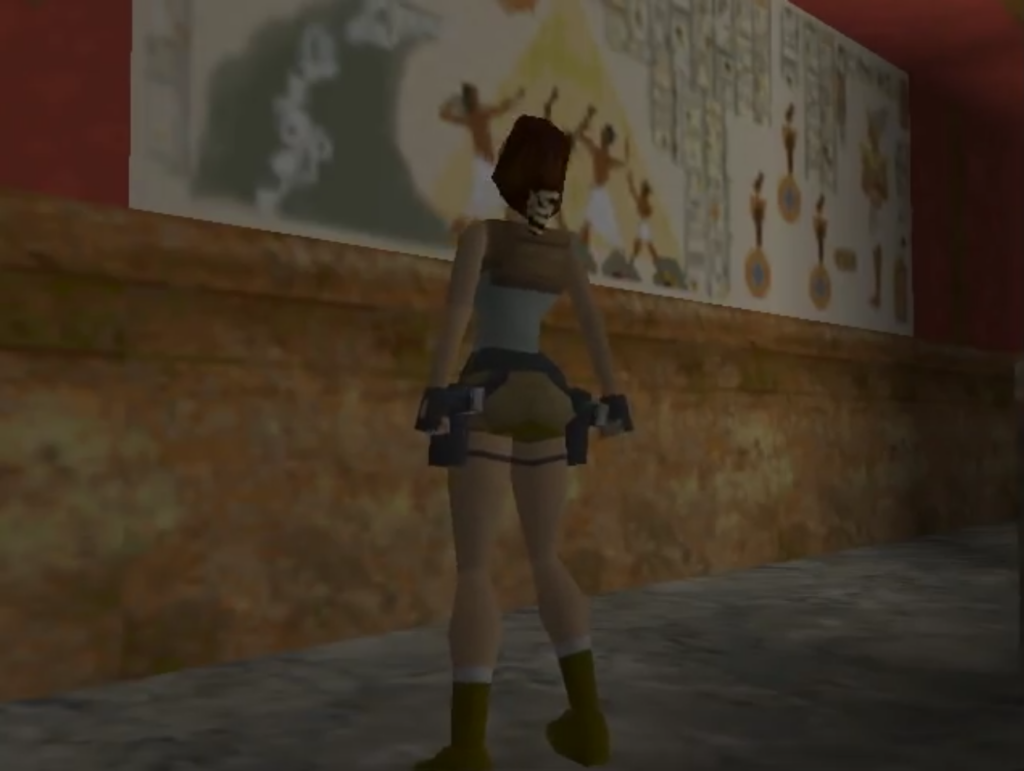

Curiously, for a game called Tomb Raider, there are surprisingly few tombs actually being raided. Each segment of the game is in fact focussed on, well, Scion Hunting, rather than the raiding of tombs. Perhaps the closest we get to actual tombs being raided is the discovery of Tihocan’s crypt (where we find the second piece of the scion). Upon discovering his tomb, the game cuts to an in-game video of Lara deciphering the images and texts located along one wall in his tomb.

For a moment Lara, rather than the player, is in the narrative driver’s seat, where she reads: “Here lies Tihocan. One of the two….just rulers of Atlantis, who…even after the curse of the continent, had…tried to keep rule here in these barren other lands. He died without child, and his…knowledge has no heritage. Look over us kindly. Tihocan.”

Of course, there is more to the game than exploration and the raiding of tombs. The game does provide player with combat. Notably, from approximately Egypt onwards, the game provides players with more opportunities for combat – with both unsettling Atlantean monsters and human foes alike. The final location in the game, Atlantis, is the most action-heavy portion of the game. And the most relentless. The final portion of the game is like a final exam, asking players to put to use all the skills they’ve honed in previous areas, to ensure Lara’s survival. There are more spiked pits, hidden boulders, booby traps, fake floors, sheer drops. The game simply throws everything at Lara in a last-ditch attempt to kill her in the most unpleasant ways possible. It’s as metal as it gets…in a Tomb Raider game, anyway.

But what’s the game like?

Well, if you haven’t found a way to mod controller support into the game, it’s going to be a 100% pure keyboard experience. For approximately 15 hours your mouse will feel alone, abandoned, and unloved. And your pinkie will get an Olympic-level workout. Remember, this is a game from 1996! The TRosettaStone Engine was built with grids in mind, so most – if not all – of the puzzles are informed by the design features of TRosettaStone – a marked difference from the Horizon Engine, which placed a greater focus on physics-based puzzles. The way in which Lara moves throughout the duration of the game and its sequels (until Angel of Darkness, which finally introduced mouse control) are therefore effectively designed to operate within a grid-based framework.

Central Themes of the Game

What does the game say? What does it make you feel?

Most, if not all art, is a conversation with the medium in which the art is created. If the first half of Tomb Raider is a reaction against action-driven popcorn cinema fare, then perhaps the second half of the game is a reaction against romanticised imaginings of Atlantis. Upon reaching the ruins of Atlantis, players are greeted with sights and sounds that are quite at odds with what might be expected. The soundtrack? The rhythm of what appears to be a beating heart, with the EQ set to ‘max subwoofer’ levels.

The sights? They perhaps tip the hat to Fantastic Voyage. Pulsating crimson walls. Stretched veins for ceilings. A visually and sonically unnerving experience, and a dramatic about-face into the realm of science-fantasy horror, full of corridors patrolled by skinless winged mutants, firebomb-hurtling centaurs, and even a skinless doppelgänger. Every new chamber and corridor reveals new ways to die a horrible death.

Screenshot courtesy of Tomb Raider Hub.)

Long gone and abandoned is the sense of wonder at exploring a lost and forgotten civilisation. Instead, we’re invited into the halls of madness. To witness first-hand the second breath of a civilisation that should be allowed to wither away and simply refuses to do so. It’s the legacy of madness writ large.

Story through art design and negative space

There is a literary/narrative theory called negative space – in short, sometimes a story reveals a theme or tells a story not through what is explained or presented, but rather, through what isn’t shown. In the art world, a common definition for negative space is “the space between objects”. When applied to gaming, it has a slightly different meaning. As described by video game journalist Patricia Hernandez, “negative space, when applied to the rule-sets of games, refers to those necessary limits that provide context for and give significance to the decisions that the player makes”. Negative space defines the scope of what we can – and conversely cannot do – in a game.

Now, games are a kind of bricolage of systems, art, music, and gameplay mechanics. It’s a powerfully interactive medium that allows us to utilise multiple sensory organs at once. And in the 90s games were still in their infancy, and game studios were still figuring out what games could and could not do as they navigated changing hardware architectures, software systems and APIs. So while genres did exist, the late 90s was a period where gameplay styles had not yet fully solidified.

As video game historian Chris Franklin pointed out in his fourth Children of Doom episode, which focused on the game Marathon, it was commonplace for games from the late 90s through to the early 2010s to feature storytelling and character building through level design scenarios and enemy placement. “A linear structure where each level contributes some plot-forwarding elements and some gameplay variations for pacing and emotional effect to reflect what’s happening in the story.”

Tomb Raider certainly fits that design. The first half of the game eases players into the gameplay mechanics, lets them explore, eases players into the different weapons, enemies, level and platforming challenges – before forcing them to put everything they’ve learned to use in the final area of the game, where absolutely everything is relentlessly thrown at players like some kind of challenge gauntlet.

But in the first half of the game puts the idea of negative space to excellent use – not only in terms of gameplay mechanics, but also narratively. Peru and Greece are presented as places that have crumbled into disuse and been abandoned. The first “stage” of the game, Peru, presents the remains of Qualopec’s kingdom[3] as full of greys, blues, and one very green and leafy valley full of – of course – dinosaurs (because what’s an adventure game without a nice tip of the hat to Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, right?).

But it’s also full of the remains of a civilisation. The detritus of the past lies strewn throughout the Peru section of the game. Lara will come across jars, bits of pottery, corpses, corridors overrun by ivy, and abandoned buildings. As the first stage of the game is set in Peru, the architectural design throughout this section of the game is meant to depict the remains of the Inca Empire. But within the game’s narrative, there’s a bit more it than that.[4]

Among the remains we also wander through, under, and over waterways and craggy, rocky ceilings that nature is slowly reclaiming. We discover mats of hay sprawled throughout old, abandoned rooms, before finally leading to a slightly more colourful palette of maroon and marigold. And eventually, a pedestal holding the first of the three pieces of the pendant that constitute the Scion of Atlantis.

But the environment? The atmosphere? Wind whistles from unseen places. A rickety bridge overlooks a room full of hungry wolves. Vines of emerald slowly overrun the remains of a ruined and/or abandoned civilisation. Bears roam freely among the remains of Qualopec’s mountain kingdom. What little music we get takes the form of obligatory action music (pulsating violins recreated on a synthesiser).

Otherwise, aside from a bit of gothic chant to lend a sense of wonder, there’s scant little noise or music aside from the crunch of Lara’s boots against rock and snow, or the sound of Lara diving into a pool of water. The open, uninhabited space in some ways feels reminiscent of a design feature used in the first Myst game: information is at a minimum, ambience is through the roof, and the imaginations of players are ignited as they are left to draw their own conclusions, and wonder about what happened.

The gameplay enables this sensory experience by not pushing players forward. It doesn’t distract or seek to alleviate boredom. It lets the player look. And feel. It lets us feel a sense of abandonment, loneliness, isolation, sadness. One of the three rulers of Atlantis attempted to preserve (it would seem) their civilisations in the Peruvian Andes, and failed. We’re invited to ruminate on a society that failed to save itself and that was ultimately forgotten.[5]

Who will remember us? What will be our legacy?

– Mikey Neumann

It’s not until we get to the tomb of Tihocan that this question really hammers the point home. Tihocan’s crypt is located underneath a monastery in Greece, and requires Lara to navigate through an assortment of puzzles, as well as rooms and corridors full of broken columns, a coliseum fallen into disuse, a cistern overtaken by nature, and finally a lone building housing what remains of Tihocan.

At the end of the Greece segment of the game, the game switches to an in-engine cutscene. The music swells. Lara looks upon a mosaic with [blurry] text. She then read what’s written, informing the viewers. It’s a passive activity. We’ve led Lara to the crypt, now she does her part in the game of telling us what we’re looking at. We’re the agent of action, and she’s the agent of information.

And this is what she tells us:

“Here lies Tihocan. One of the two just rulers of Atlantis, who even after the curse of the continent had tried to keep rule here in these barren other lands. He died without child, and his knowledge has no heritage. Look over us kindly. Tihocan.”

Intimations of concerns around a legacy, remembrance, memory. Who will remember us? What will be our legacy?

However accidental it might have been, it’s impossible to ignore that a cohesive set of themes does begin to emerge when one starts putting aspects of Tomb Raider’s gameplay and design under a microscope. A palpable sense of sadness arises from the level design and object placement and is even expressed, however briefly, by the game’s central antagonist. Late in the game, Lara and Natla finally meet face to face on an island that’s suggested to be part of a larger network of what we might call the ruins of Atlantis and Natla expresses, amid frothy, dim-witted rants about the survival of the fittest and the waning of the species, a rather sudden and sad sentiment: “The cataclysm of Atlantis struck a race of languoring [sic] wimps; plummeted them to the very basics of survival again. It shouldn’t happen like that.”

Yes, Natla’s a bug-fuck insane Atlantean that was put on ice for possibly thousands of years by Qualopec and Tihocan. Yet for a moment, she manages to express a profoundly human sadness. For a scant, brief moment, she elicits pathos. Her singular moment of decency is a summation of the themes that have been presented to players through the art design and exploration gameplay mechanic. It’s the sadness of collapsed civilisations, of what was lost – of what we lost.

By the time she utters these sentiments, the player has played through roughly 90% of a game that is approximately 16-17 hours in length, and as a result has had a chance to witness firsthand the decline alluded to in the line “plummeted them to the very basics of survival” (recall that the narrative implied Atlantis as having been a technologically advanced society).

That Which Remains

Sadness is arguably the theme at the very centre of this game. After having spent 15 or more hours exploring civilisations that have collapsed, players are presented with an antagonist who says that “it shouldn’t happen like that” – an expression of sadness at the collapse of civilisations. They could have been saved – maybe. But their passing is still expressed as being profoundly sad.

This sadness is reflected in the design of the first half of the game. Don’t believe me? Look at it again. Peru: abandoned buildings, rooms, huts and reliquaries. Collapsed bridges, structures that have been taken over by nature, as ivy clings to the sides of walls and grass shoots out of doorways. In Greece, columns have fallen over, doorways appear rusted and decayed. Gorillas, crocodiles, rats, lions, panthers, and bats all make appearances, reiterating the idea that nature has started to reclaim that which remains.

There’s less sign of human habitation here. No shelters, tents, fires, or tools remain to convey a sense of former human habitation. Instead, we get a world that’s been emptied of human inhabitants. Perhaps the closest we get to anything suggesting human settlement is a level named ‘The Cistern’– a beautiful area whose colour palette is interestingly reminiscent (perhaps intentionally) of the Peru levels. I’ve come to wonder if it was meant to be a visual clue, suggesting a shared history between the two remaining rulers of Atlantis.

Again, bearing in mind the design and technology limitations of 1996, this might be reaching. But it’s fun to think about, given the storytelling restrictions of the time.

The Nightmare at the End of the Tunnel

It’s only after we leave Greece and arrive in Egypt that things take a sharp right turn into a Giger nightmare with the lights turned on. The third piece of the scion is located in a region that, to the best of our knowledge, wasn’t ruled over by any Atlantean. An in-game FMV poetically shows the third piece being tossed to the wind, not unlike Maglor throwing his Silmaril into the sea.[6]

And for reasons that are never quite made clear, players are given their first encounter with Atlantean creatures in Egypt. Did Natla create them following her escape from stasis in Nevada back in the mid-20th Century? Did they somehow manage to survive being captured after Natla’s downfall in Atlantis, presumably thousands of years ago? It’s really not clear.

Egypt is where the game shifts its tone. It’s not that Egypt doesn’t feel like a place whose inhabitants have abandoned it. In fact, it doesn’t even feel abandoned. A pristine sheen remains over most if not all of the walls. Frescoes abound. It feels more like the idea of Egypt than a formerly inhabited location.

It’s also at this point in the game where the puzzles start to become worryingly tedious and frustrating, and involve an increased amount of back-tracking. I increasingly found myself wondering about the purpose of any of the rooms, and asking myself “who lived here? Where did they sleep?” It’s at this half-way point that the game slowly pivots to a more action-oriented style of gameplay, where player responsiveness takes on an increased level of importance as the game begins to escalate and moves away from the slower, ambient tone that dominated in the first half of the game.

It’s interesting to wonder if the developers were engaged in a thought experiment about the rise and fall of civilisations. If all civilisations wax and wane, if they all have their time in the sun before exiting stage left, are the Atlantean mutants that linger about Egypt and throughout the island ruins of Atlantis metaphors for the mental decay of Natla? The game gives us plenty of negative space to fill in, but also leaves us feeling a certain way about the world we’re exploring.

The Potemkin Effect: The Legend-era Remake

Legends and Anniversaries

It’s difficult to talk about the original Tomb Raider without addressing the 2006-7 anniversary edition produced by Crystal Dynamics and Toby Gard, the creator of Tomb Raider – who famously left Core Design after the release of the first game. It would not be until Tomb Raider Legends that he would return to the franchise he created – initially as a creative consultant. However, “his work became ‘hands on’ during the production and eventually included Lara’s visual redesign, overseeing character design and creation, co-writing the story, designing and implementing parts of the character movement system, and directing the cinematics”[7].

Once Crystal Dynamics completed work on Tomb Raider Legends, work began on a 10th anniversary edition of Tomb Raider that would tie directly into the storyline begun in Legends. To their benefit, Crystal Dynamics managed to convince Lara Croft creator Toby Gard to expand upon the narrative established in the 1996 game.

How It Differs

Let’s make this clear right away: Tomb Raider Anniversary is not a one-for-one remake. Entire sections of the game have been shortened, tweaked, modified, and otherwise made to change the focus of the game from exploration to adventuring.

Some of the more die-hard fans of the franchise have done commendable work in going through both games and writing up the differences between the original and the anniversary edition. A comprehensive post on Reddit (preserved by laracroftonline) providing a list of the changes made it clear to users interested in playing through the anniversary edition that: “this is not a 1:1 remake of the original Tomb Raider (TR1). Crystal Dynamics has not only rebuilt the game from the ground up–improving on TR1’s visuals–but they also added a good amount of new content; yet in the process, they removed a great deal of old locales from the original. Overall, the game is shorter and some of the puzzles have been simplified from the original 1996 version (although some have been improved)”.

Sound Design

An interview with the composer and sound designers at Crystal Dynamics provides a clear understanding of the sonic shift that could be expected in this new iteration of Lara Croft. Composer Troels Brun Folmann stated a desire to convey a sense of adventure with his music, while Mike Peaslee, the game’s sound designer, said “without audio things seem dead and repetitive”.

This statement is quite at odds with the original Tomb Raider, which was notoriously quiet and filled primarily with natural ambient sounds. There was, of course, the sound of Lara’s footsteps or that of wild animals attempting to turn Lara Croft into their afternoon snack. And aside from the occasional moment during which Nathan McCree’s oboe-led theme appeared, much of the game was silent. Anniversary shifts gears considerably, with sound that’s much more involved in every aspect of the gameplay. Quiet moments are few and far between in this adventure.

Level Design

A new engine – the Horizon Engine – means new points of focus and design interest. With Legends, Crystal Dynamics introduced a grappling hook and skilfully integrated it into the reimagined designs featured in Anniversary. Though Anniversary it is arguably prettier as a result of having access to more contemporary graphical features (circa 2007) there was, as always, a price to be paid for beauty. In this particular instance – the scale and size of levels suffered. A not uncommon observation among some players was that levels felt reduced in scale, more claustrophobic, and narrower. Although some areas were increased in scale (e.g. a waterfall in Peru), others felt smaller or more streamlined, as was the case with the Lost Valley. What was once an open and expansive location with multiple tunnels, waterfall, and rope bridge was now little more than a circular area with a bit of platforming on the side.

The village of Vilcabamba in Peru was also observed as having been reduced in scale. Also changed was the swimming mechanic, with the length of time that Lara could hold her breath being shortened. The knock-on effect from that decision? The underwater portions of the game were notably shrunken down. And in keeping with a gaming trend at the time that had been kicked off with Shenmue, Anniversary featured Quick Time Events.

Admittedly, the goal with Anniversary seems to have been to convey a sense or feel of location rather than a location itself. Combined with the need to push the player forwards, reduced size and scale of locations, and more action-oriented gameplay, the locations in Anniversary feel – if anything – more like a theme park than an actual place. It’s a digital Potemkin Effect[8], as the mechanics inform level design rather than the inverse. Sadly, despite the reduction in the scale of the levels, the number of enemy encounters does not seem to have changed much, resulting in the game feeling more action-oriented than the original.

This, combined with the integration of “checkpoints” – a feature that would appear in all subsequent Crystal Dynamics iterations of Lara – would result in a somewhat changed beast. Though players could save absolutely anywhere, each and every save game would load at the nearest checkpoint in the game world, resulting in players having to redo entire sections multiple times. Some of these cases might only add a few seconds of extra gameplay, but some might take longer – especially during scripted sequences (sometimes called “on the rails sequences”).

While the Core Series was by no means a systemised game series in the spirit of immersive sim “0451” games, they did at the very least avoid the use of Quick Time Events and heavily scripted sequences – features that would appear in both the Legend and Survivor iterations, much to the frustration of some gamers who found the addition of this gameplay mechanic unnecessary and frustrating.

Art can be a happy accident. Regardless of the medium an artistic piece is created, and the artist hopes it will mean something to someone. Hopes their efforts were not in vain. In the world of gaming, we’re still figuring out how to talk about the medium in a meaningful way. And despite assorted scandals, accusations of gatekeeping, pushback towards academic analyses, and other issues, continued analyses are not likely to diminish. Either we acknowledge that game creation is an art and thus merits critical analysis, or we accept that it is not an art and therefore doesn’t merit being researched and discussed.

The first Tomb Raider is a game that asks players to engage in a specific set of gameplay mechanics, observe artistically rendered environments, listen to a specially-crafted musical score, and study and learn about a forgotten – and imagined – history. The journey across Peru, Greece, Egypt, and finally the remains of Atlantis is an auditory, kinaesthetic, visual, and emotional experience. And though, like many other artistic works in other media, it was inspired by works that came before it,[9] Tomb Raider was ultimately a unique and masterful experience that took the best of what came before and built upon it to create a wholly new and unique experience. A unique experience that arguably has not been replicated by any of the subsequent sequels.

[1] There’s an argument to be made that public perceptions of how big a game should be allowed to get now dictate storage usage.

[2] Interestingly, 2018’s Shadow of the Tomb Raider, the final instalment in the Survivor trilogy, features Lara travelling to the Peruvian city of Paititi – a legendary lost Inca city. Whether or not this was an intentional nod to the original Tomb Raider is unclear.

[3] Let’s call it that, for the purposes of thematic exploration.

[4] Interestingly, the Tomb Raider wiki at tombraider.fandom.com suggests “After the destruction of Atlantis, he [Qualopec] escaped to Peru, where he presumably tried to re-establish his civilization. The result was the birth of the Incas.”

[5] Croft creator Toby Gard pointed out in an interview that “one of the main reasons the original game was set underground was because we couldn’t really do a convincing outside”.

[6] You’re welcome, Tolkien fans.

[7] https://www.linkedin.com/in/toby-gard-5520b67/

[8] Referring to the famous Potemkin village – where a construct’s sole purpose is to provide a façade.

[9] Creator Toby Gard has cited Prince of Persia, Ultima Underworld, Virtua Fighter, the Indiana Jones films, Tank Girl, and Hard Boiled as works that had a direct influence upon the creation of Tomb Raider.

(A great many thanks to Andrew “Edpool” Hindle for his editing efforts on this project. I couldn’t ask for a better – and funnier! – editor. Andrew “Edpool” Hindle can be found on Twitter @St_EdPool. His blog is www.hatboy.blog and his books are available here.)